The Strait Hop: Determination, Creativity, Hutzpah and Dishonesty

Once again I found myself in Moscow. A few days before, I had received a telegram from the Soviet Peace Committee to accept an award for my work in opening the Alaska – USSR border. I was asked to attend the American – Soviet Peace Conference in Moscow. I would share the award with Gennadi Gerasimov, the USSR foreign affairs spokesman. It was 1990, the tail end of the Cold War.

I later learned that the Peace Committee was part of the KGB, prompting Alaska friends to entertain themselves by introducing me as a recipient of a KGB prize. This was not a compliment.

I was living in Juneau, Alaska and was, as usual, dead broke. Someone had provided an airline ticket to Russia. Once in Moscow, there were friends to stay with.

After an exhaustive trip halfway around the world, I was happy to see Lily Golden at the gate. Lily was my patient Russian hostess over the years with an incredible family history. She was born in Russia to an African-American professor from the American South and his Jewish Polish-American wife.

Lily’s flat was a status symbol by 1980’s Soviet standards. To me it, unfortunately, looked like an American tenement. After a few years of staying there on and off, it seemed large and luxurious in comparison with other flats.

Her flat was in a gray concrete high rise near the center of Moscow. The front door was locked and I never had a key. I opened it by sticking my hand through a broken window to reach the inside lock. Continual prayer was needed to get the shaking elevator all the way to the fifth floor. I slept on a narrow and very lumpy living room couch. Turning over required first waking up so one didn’t roll onto the floor.

After the peace conference, Lily asked me to visit Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, where she was raised, so I could meet family friends.

Creative Russians had wrangled an internal passport for me, which I did not qualify for and could not legally possess. One needed to be Russian to own one. The risk was worth it. This passport allowed me to fly and take trains as a Soviet citizen, paying only a few rubles in fare, rather than the hundreds charged to foreign travelers. That was the only way I could afford to travel across such a vast country. The trick was to get myself on and off planes and trains without speaking a word of English. Or Russian, which I did not speak.

I managed, with help. Russians appeared when I needed them.

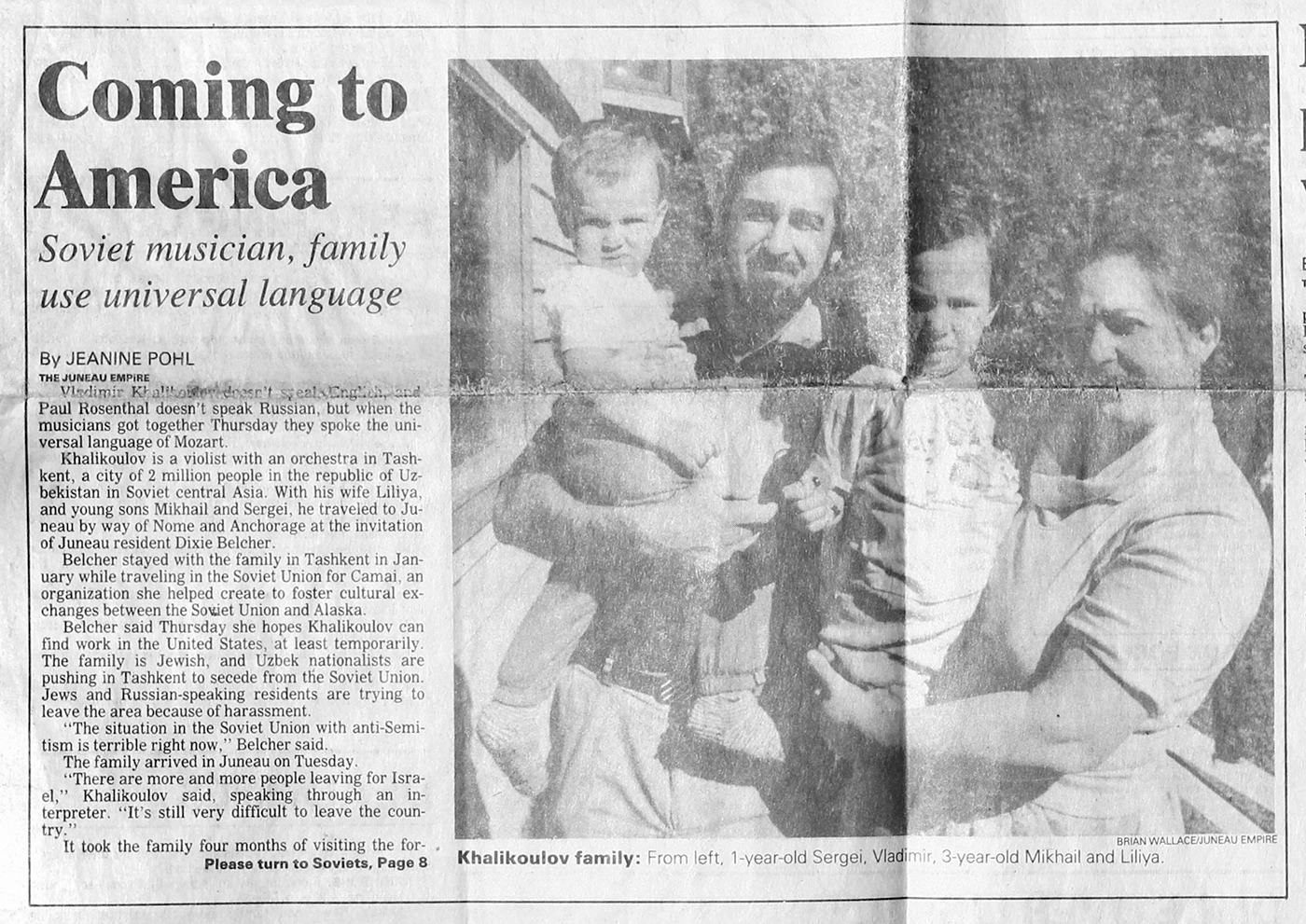

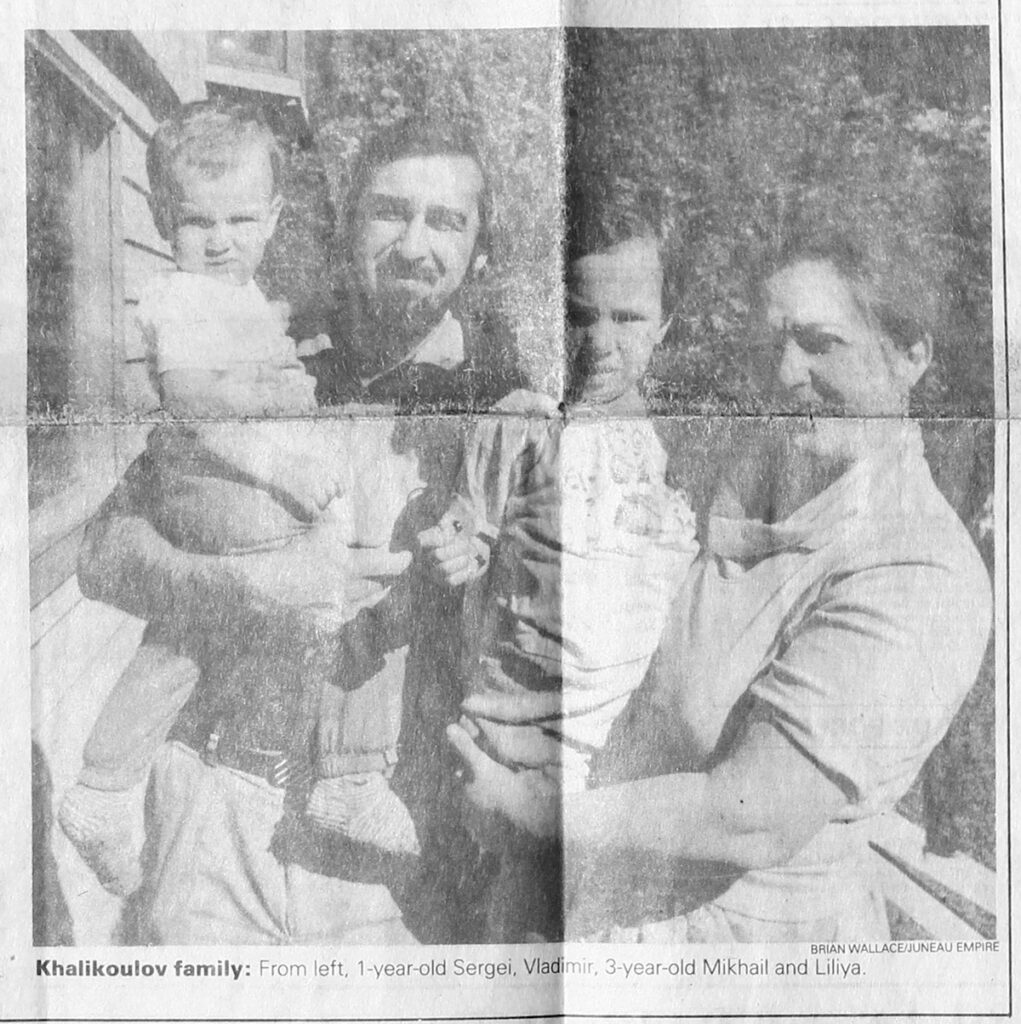

I was met in Tashkent by Volodya Khalikoulov, a tall, dark good-looking man in his thirties, a violist for the Tashkent Symphony. Next to him was Liliya, his shorter and rounder wife, who held a master’s degree in music history. Tagging along were their two rambunctious boys, aged one and three. This was my host family.

Uzbekistan was one of five Soviet republics in Central Asia. Most Uzbekistanis are Uzbeks and Muslim, with their own culture, music, art, food, architecture, language and history. They didn’t like being ruled by the communist atheist Russians. There was palpable anger toward them.

To make things worse, Volodya and his family were Jewish. Anti-Semitism was rife, as it was in the rest of the Soviet Union. They and their Jewish friends were terrified. They took us to a meeting of several hundred Tashkent Jews that focused on ways to escape. Fear was everywhere.

I decided I would try to help my host family.

I was without money, but had learned considerable creativity from my Russian friends. Russians take pride in circumnavigating laws, authority and bureaucracy, mostly out of necessity, but sometimes just for fun.

After some consideration, I decided I would get the Khahikoulov family out of Tashkent and into Alaska. They said they had relatives in California. Maybe I could find a way to get them all the way there?

I told them to expect a telegram from me with a made-up invitation. I had no idea what it might say.

For a little bit of money my family could fly to Provideniya, a small port town in the Russian Far East. Provideniya, meaning “providence” in Russian, was a short 50 mile hop across the Bering Strait to Nome, Alaska. Then another 1,500 miles to Juneau.

Back home in Alaska, I brainstormed my options. Volodya was a musician. What if I invited them to a music event? This just might work.

I sent them a telegram. On it, I introduced myself as a member of an association called “Families of American and Russian Musicians”. The telegram was an invitation to the association’s conference in Alaska. It was, of course, a non-existent association. Russians had taught me well. Volodya would be carrying his viola, making him look like they really were going to a music conference.

I held my breath that this would work with the American consulate and Alaska border agents.

It worked perfectly.

Since I was doing this without money – any money – I asked the Anchorage Jewish community if they could fund tickets for the family from Nome to Juneau, which they did.

I had no idea when – or if – they might show up. There were no cell phones, of course. A landline phone call between the US and the USSR in 1990 had to be routed through a Pennsylvania operator. It took a minimum of nine hours to reserve a call – and when it went through, someone needed to be there to pick up. If no one answered, one waited another nine hours.

One day a woman who spoke both English and Russian called from Nome: “There is a Russian family here. They’ve just arrived. They say they are somehow connected to you?” Which is how I found out that my family had made it to Alaska.

Alaska Airlines miraculously overbooked their flight from Nome to Juneau, apologizing with four free tickets for them to fly anywhere served by the company. Those tickets came in handy later.

Once in Juneau, Joyanne Bloom, a member of the Jewish community, took them under her wing, a mission of love, as energy shot from every pore of the two little boys. Two months later, the family used their free tickets to fly to San Francisco where they had cousins they could stay with and where Volodya could find work in an orchestra.

I visited them years later. Volodya was happily selling pizza while his wife sold boys’ underwear in a department store. It was one of the boys’ birthdays. He was already 22. A big sheet of plywood sat in the living room, laden with Russian food, vodka and Russians. A bit of Russia in the middle of San Francisco.

Volodya finally got a job in a symphony and the family became U.S. citizens – a process helped along, I’m sure, by Russians’ genetic abilities to navigate bureaucracy.

It’s amazing what one can accomplish without money. Determination, creativity, hutzpah and dishonesty can go a long way.